MORGANTOWN, WV — West Virginia University researchers are developing a sleep apnea detection device that patients can use at home, aiming to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of the disease. This project is being supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant.

Dr. Sunil Sharma, N. Leroy Lapp Professor and division chief of the Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine Fellowship Program at WVU’s School of Medicine, received the award after collaborating with other WVU researchers to develop prototypes and secure a patent.

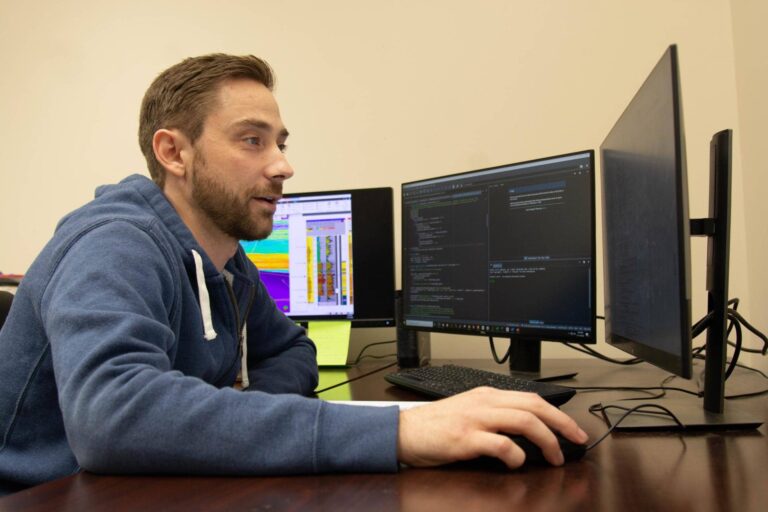

“It’s about taking technology from the lab to the bedside,” Sharma said. “This grant will help us connect with people who have a high level of expertise and join their strengths with ours. We will work with experts in AI, software production and enhancement, industrial production, and technology and hardware enhancement.”

With NSF Innovation Corps program support, these prototypes include a watch and a fingertip clip, similar to a pulse oximeter, that patients can wear while sleeping at home. They use artificial intelligence to analyze data collected via an app on a smartphone or tablet.

“What the devices do is collect information from your bloodstream regarding the certain way the oxygen is delivered and circulated in the blood,” Sharma explained. “Based on those oxygen signals and the algorithms which we have fed in — the way we designed it and calibrated it — they can accurately reflect what may be happening in the body without having to go through very expensive testing.”

Sharma noted that beyond detecting the presence of sleep apnea, the technology also indicates the severity of the disorder, which helps determine if patients need treatments like continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or simple lifestyle changes.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common condition where the airways partially or completely collapse, decreasing oxygen saturation. Symptoms include loud snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness, but many people are asymptomatic. About 80% of OSA cases worldwide remain undiagnosed.

“A delayed diagnosis can lead to worsening of underlying comorbid conditions such as heart failure, stroke, and atrial fibrillation because OSA acts like a fuel to other diseases,” Sharma said.

The at-home device follows a five-year study by Sharma and colleagues at WVU Medicine J.W. Ruby Memorial Hospital. The study screened patients hospitalized for general medical and heart failure conditions to determine if they should be tested further for OSA. Those diagnosed received positive airway pressure therapy and were instructed to use it consistently. Researchers found that non-adherent patients had significantly higher hospital readmissions and emergency room visits than those who adhered to the therapy.

“The above data complimented by similar findings at other institutions strongly suggest that if we catch OSA earlier, the treatment may facilitate in the control of their comorbid conditions,” Sharma said.

Published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, the study also indicated that early detection and treatment reduced health care costs and hospital resource use. With fewer people needing hospitalization, more beds were available for other patients.

The disorder often goes undetected due to a lack of sleep physicians and lab facilities, low awareness, and associated patient costs. “Sleep labs are so booked that sometimes it takes weeks to months to get an appointment. In that amount of time, they’re possibly seeing readmission to the hospital and a significant escalation of their condition,” Sharma said.

At-home testing is more appealing to patients who do not want to spend the night in an unfamiliar setting, which can affect sleep quality. It is also beneficial for rural residents who may have to travel long distances to a testing site.

Sharma hopes the study raises awareness that early detection of OSA can improve patient outcomes and prevent the development of more serious conditions.

“We are just learning more and more about this disease, how it drives other conditions and how patients can be very asymptomatic and yet have the disease still going on in their system,” he said. “We do know we can’t treat it if we can’t detect it.”