BUCKHANNON — Statins and beta blockers are infiltrating the aquatic ecosystem, according to West Virginia University researchers who have detected these cardiovascular drugs in fish collected from two West Virginia rivers.

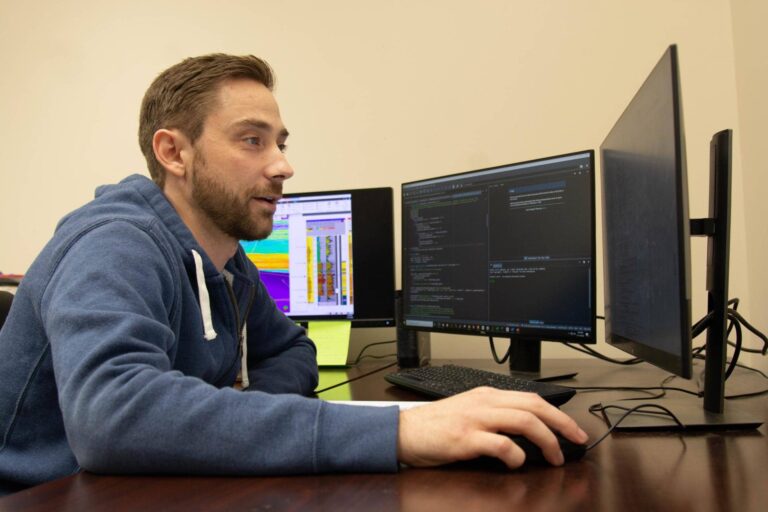

Joseph Kingsbury, a doctoral student in natural resources science, and Kyle Hartman, professor of wildlife and fisheries resources at the WVU Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Design, carried out a study revealing the presence of these pharmaceuticals in fish from the West Fork and Tygart Valley rivers near Weston and Elkins, respectively.

Beta blockers are used to treat high blood pressure, while statins prevent cholesterol synthesis. Both drugs are commonly prescribed for heart disease and other cardiovascular conditions.

Water treatment facilities, which aren’t effective at removing these compounds, consistently discharge pharmaceuticals into waterways. Although the drugs break down quickly, their widespread use means they are continuously reintroduced into the environment.

Kingsbury, hailing from Aurora, Illinois, studied these as emerging contaminants. “With contaminants, the first place we always start is where they’re coming from,” he said. “Can we isolate those sources? Does it come from us? Not so much chemical plants, but from individual humans. We ingest the drugs, we partially digest them and then we excrete active variants.”

Humans take these medications to lower LDL cholesterol, while fish produce cholesterol to store lipids. “For us, lipids are often considered bad,” Hartman said. “But lipids get fish through the winter and lean times. I was concerned we might be seeing eroding fish populations and not really have any idea why, because it’s not outright killing them.”

The researchers examined the concentrations of these drugs in waterways and studied fish health relative to these pharmaceutical levels, both upstream and downstream of discharge sites, as well as within the discharge areas.

Treated water is typically discharged from a straight pipe into the river, where fish tend to gather near the warm water flow and may use artificial habitats set up to prevent erosion.

Models created by the researchers demonstrated how drug concentrations vary by location and water quality parameters such as temperature, pH, and conductivity. The initial study results showed significant accumulation of certain statins in fish, with some bioaccumulating at unexpectedly high rates.

“Pharmaceuticals are a unique contaminant designed to alter our bodies through specific chemical pathways,” Kingsbury said. “Fish are vertebrates, they have a lot of the same preserved biological pathways that we have. So, it doesn’t take a very high concentration to alter their biological systems.”

Fish livers, like human livers, process toxins. Beta blockers and statins are metabolized in the liver and accumulate there. Kingsbury and Hartman found liver damage in some fish, with discolored organs and parasites. “None looked super healthy compared to traditional fish livers,” Kingsbury said. “And pharmaceuticals are very resilient. They’re meant to be saved, to go on our shelves and not break down over the years. We found quite a few sub-lethal effects.”

Working with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, Kingsbury collected fish from 21 different species in the two rivers, examining organ size, organ weight, and overall condition. “The models showed us that certain drugs affect certain classifications of fish differently, in terms of overall health,” he said.

Kingsbury also collaborated with David Sanchez of the University of Pittsburgh’s chemistry department to develop a new method for detecting statins in fish, focusing on potential effects on fish eggs.

As research continues, Kingsbury aims to analyze larger sample sizes to precisely determine effects, particularly on reproduction—eggs and embryos. Initial studies suggest behavioral changes in animals due to these drugs, but the minimum dose to elicit such a response remains unknown.

Kingsbury’s major concern is long-term, multigenerational exposure. “Pharmaceuticals are notorious for altering our DNA,” he said. “Fish are no different.”

Future research will involve designing long-term laboratory exposure studies to examine chronic toxicity across generations. Researchers also aim to enhance their detection methods for the top five statins in the aquatic ecosystem.

Hartman and Kingsbury hope their findings will guide physicians towards compounds that are less harmful to the environment. “We’d love to be able to help companies and those who make the decisions be more aware of what happens when they introduce these drugs to market,” Kingsbury said.